Cardinal: Symbol of Economic Transformation and Resilience

Cardinal isn’t just a place to get a beer—it’s a story about what happens when people decide to put down roots with purpose. Briana Doyle and Will Tomkinson didn’t come to Hudson to join a sleepy town; they came to co-create something new. They left the Vancouver market for the peri-urban edges of Montreal, bringing with them political literacy, entrepreneurial vision, and a desire to build resilient community infrastructure—culturally and economically. That’s how Cardinal was born—right in the middle of a pandemic, carved out of an old gas station and body shop at the heart of our village.

Their values weren’t performative. They had been living in Peter Julian’s riding of New Westminster, under the NDP banner, and arrived in Vaudreuil-Soulanges with the same sense of civic engagement. Briana and Will understood something crucial: democracy begins where you live, and politics should show up in public life, not just at election time. So when they organized a candidate meet-and-greet this week—what they called “Brews on Tues”—it wasn’t a stunt. It was an offering.

I walked in not just as a voter, but as someone who’s stood on the other side of these gatherings. We used to have more formal debates in Hudson—packed houses at the community centre, smart questions from residents, and seasoned moderators like Jim Duff of The Lake of Two Mountains Gazette. Later, Carmen Fabio,

Pat O’Grady and Your Local Journal carried the torch. These were the forums where ideas were tested and trust was built. Duff especially had a nose for calling out political theatre. Like a good journalist, he cut through the noise. He hated acclamations and asked better questions than most hosts on national networks.

This event was different, less structured—but that wasn’t a bad thing. It was candid, civil, and hosted with integrity. And still, something was missing.

Peter Schiefke (Liberal), Thomas Massé (Conservative), Christophe Massé (Bloc), and Dave Hamelin-Schuilenburg (Green) showed up. The NDP candidate didn’t. Maybe the assumption is that the Jagmeet effect will hold—that enough voters will check the orange box no matter who carries the flag here. But the absence still stung. In the absence of debate, even presence starts to feel hollow.

I spoke with everyone except the Bloc candidate. He didn’t come to me, and I didn’t go to him. Not out of hostility—just quiet disinterest. That moment, standing in a room with four candidates and still feeling politically orphaned, summed it up. I’ve been watching closely. I’ve been asking questions. I’ve read the leaflets. And I’m still undecided.

The Literature of No Vision

After the event, I took the pamphlets home like field notes. In theory, this is where a campaign stakes its claim—where we see not just what a candidate stands against, but what they stand for. But flipping through them under the kitchen light, I realized how hollow this genre has become. These weren’t manifestos. They weren’t invitations to imagine a better future. They were bullet points and blame.

Let’s start with the Conservatives.

The front of their leaflet features four pledges: Axe the Tax. Build the Homes. Fix the Budget. Stop the Crime. It’s the kind of language designed to sound decisive without saying much. “Common sense conservatives” will do all these things—but how, with what trade-offs, at what cost, or in what timeline, is never clear. If you’re explaining, you’re losing, as the saying goes. But if you’re not explaining, you’re treating voters like they don’t deserve the details.

The back of the pamphlet is a study in political contrast—literally. The blue side is framed as the solution: cut taxes, bring down inflation, impose a dollar-for-dollar law to offset new spending with cuts, and “bring home lower prices for Canadians.” It sounds like fiscal magic, until you consider how abstract these terms become without specifics.

Then comes the red side: a screed against the “Carney-Trudeau Liberals.” It’s a greatest-hits compilation of economic grievances—80% of middle-class families paying more taxes, $800 more in annual food costs, two million food bank visits in a single month, skyrocketing housing prices, and the spectre of $700 billion in new debt. At the bottom, in bold: “Carney. Trudeau’s chief economic advisor.” It’s not subtle. The villain has been cast, the script is ready, and your job as a voter is to fear.

But fear is not a plan. And the Conservative candidate, clearly aware of this, seemed sheepish about the attack politics side of his pamphlet. My take, they all do it at some point—you either say no to the party or you wear their message.

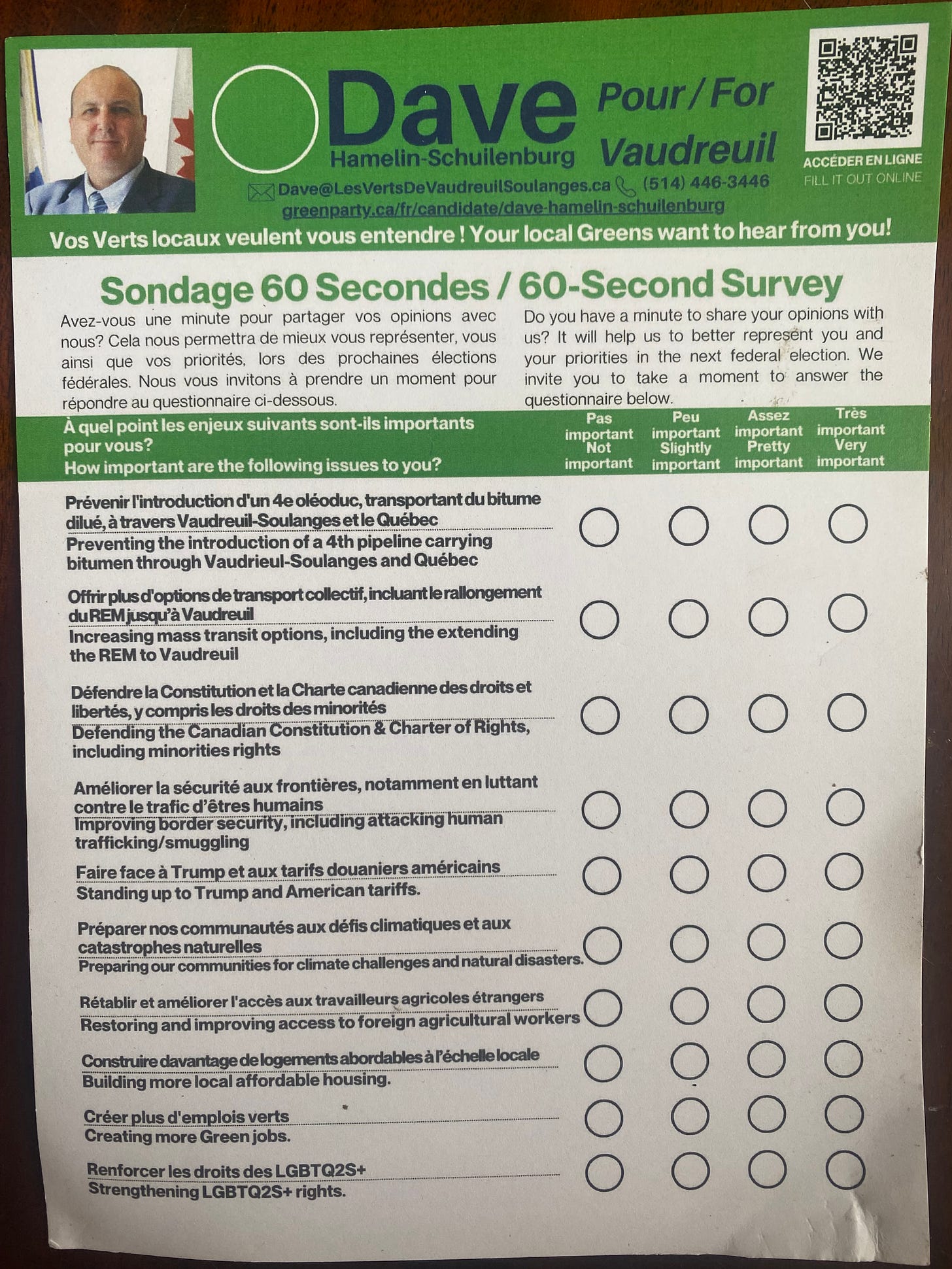

Then there was the Green Party’s pamphlet—earnest, well-meaning, and entirely swallowed by form. Ten questions posed as a multiple choice survey. The final two: Create more green jobs? Strengthen LGBTQ2S+ rights? Then a blank line on the back asking what issue matters most to you. I admire the democratic impulse behind it—it invites dialogue, not direction. But it also fails to signal confidence or coherence. The message becomes the medium, and in this case, the medium is… a pop quiz. But I like Dave and he is travelling with fellow candidates with other ridings which shows a team spirit amongst the Greens.

The Liberals didn’t bring a handout, (or I didn’t get one) but Peter Schiefke spoke about the future under a Carney government, and how its focus would be to “grow the economy.” But at some point, you have to ask: What are we measuring when we measure growth? If the goal is GDP for GDP’s sake, we’ve learned nothing. If we’re not using different metrics—wellbeing, environmental impact, social equity—then we’re just rearranging deck chairs on a ship powered by stock buybacks. Carney’s book Values goes a bit into ifusing values into capital and avoiding market fundamentalism—but who will decide the values and how will they be integrated into our liberal democratic system already under the stress of illiberal populism.

Each of these approaches reveals something deeper about how campaigns are run. The Conservatives are running a fear-forward, message-disciplined campaign that’s heavy on emotional trigger words and light on substance. The Greens are running on trust and process, but the message is buried in the form. The Liberals, after nearly a decade in power, seem to assume that institutional legitimacy and economic jargon will do the job. And the NDP? Not even physically present.

This is what political professionalization has delivered: not better ideas, just safer ones. Not bolder choices, just blander ones. When everything is about optics and offense-avoidance, you stop speaking in full sentences. You reduce the act of persuasion to the most frictionless possible contact.

And yet, I’m not disengaged. I’m just unconvinced.

Peter Schiefke, in fairness, brought something different in 2015. His campaign was fresh, multigenerational, driven by young people and a sense of positive politics. It wasn’t just electoral machinery—it was storytelling, framed around hope. It’s hard to argue with someone who consistently tries to meet people in a positive frame. Even when anger approaches, he absorbs it and responds with optimism. It’s a good quality to have in a politician. It makes people feel heard, if only momentarily.

But not everyone feels understood.

That’s the dilemma. When politics becomes relentlessly positive, there’s little space for difficult truths. Small minorities with big problems—those whose needs don’t fit neatly into the messaging arc—risk being smoothed over or forgotten. That’s not necessarily malice; it’s strategy. In an election, time is short and votes are scarce. You prioritize constituencies you can win or keep. It’s not personal. But it is political.

And politics—real politics—requires the imagination to build what doesn’t exist yet.

Back in 2011, in the wake of that historic election, I gave a speech in Pointe-des-Cascades outlining seven sustainability strategies for Vaudreuil-Soulanges. One of the most important was a bold vision for regional public transit—an investment that could transform how people live, work, and move in this region. Olivia Chow and I helped flesh out the study for a National Public Transit Strategy at committee. It remains long overdue.

Yes, the Liberals have since made catch-up investments, and they matter. But big vision requires more than funding. It takes political commitment to reimagine the everyday—and the courage to move past the “pragmatic” idea that car culture is fixed and eternal. That’s where the Conservative frame often lands: we drive here, it’s who we are, let’s work with what we have. It’s tidy. It’s realistic. But it surrenders the possibility of something more.

That’s the erosion I feel now—not of hope, but of imagination. Of the willingness to speak into uncertainty, to say: This may be hard, but it’s worth it. Not because it polls well. Not because it’s costed to the decimal. But because it’s what’s needed.

Still Undecided? Maybe That’s the Point.

There’s a certain shame assigned to being undecided. As if indecision signals ignorance. As if to be unsure is to be unprincipled. But maybe indecision, in a time like this, is not a failure of clarity. Maybe it’s a quiet form of discernment.

We are saturated with messaging. Bombarded by platforms, pledges, slogans, threats. But the one thing we’re offered too little of is time to think, to feel, to weigh not just what candidates say, but whether those words connect to something deeper—something human, coherent, even beautiful.

I’m undecided not because I’m disengaged, but because I still believe this matters. Because I don’t want to vote for a brand. I want to vote for someone who risks telling the truth plainly. Someone who respects the intelligence of a weary public. Someone who can admit where things are broken and still offer a reason to keep building.

Too many campaigns confuse clarity with simplicity. They avoid the mess, the complexity, the paradox. But that’s where real leadership lives—where we admit that the same policy that helps some might alienate others, that some investments won’t yield headlines but will make life more livable. That some problems can’t be solved by governing within the grooves of what already exists.

I don’t expect perfection. I don’t expect poetry. But I do expect the courage to ask better questions. And to stop pretending that politics has to be either technocratic management or weaponized grievance.

So yes, I’m still undecided. But I’m not lost. I’m listening. And I’m waiting—not for a hero, but for someone who is brave enough to mean what they say.

If this resonated with you, subscribe to The Strategic Wordsmith for more principled, plainspoken political analysis rooted in place, memory, and the courage to imagine something better.

Thoughtful. You bring the reader inside the dilemma of voting authentically in turbulent times.